Just breathe. If detecting lung infections were as simple as taking a breath, patients with cystic fibrosis would be able to seek treatment sooner.

People with cystic fibrosis who get bacterial infections in their lungs often experience a decline in their lung health — which ultimately shortens their life spans. However, if the infections are caught and treated early enough, these same patients can live longer, healthier lives.

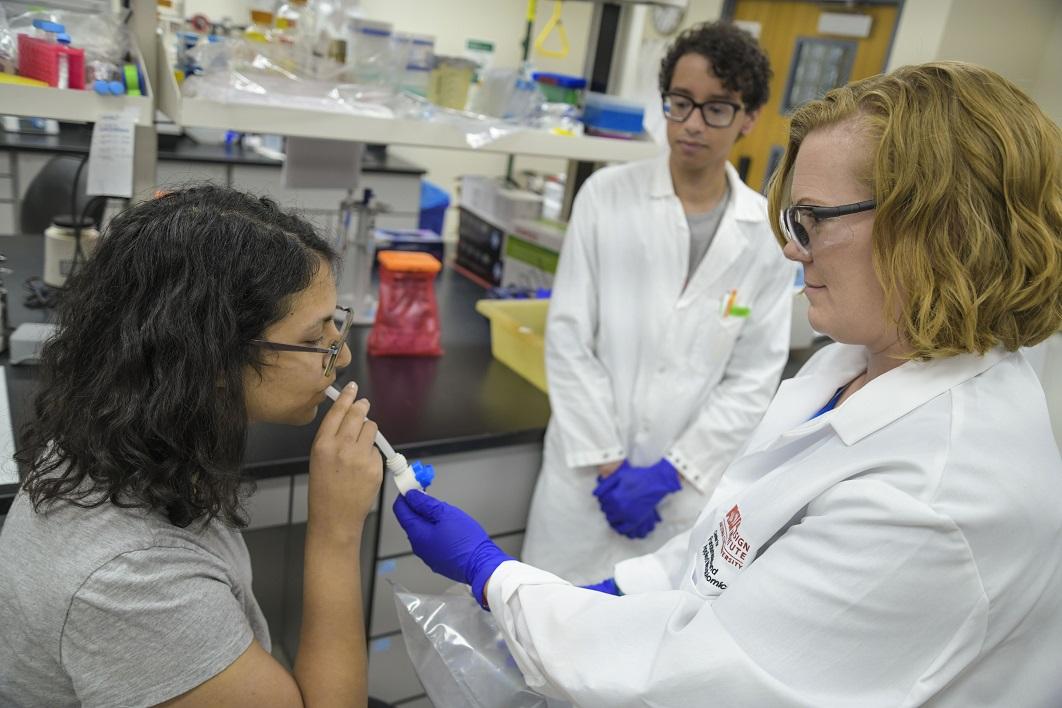

School of Life Sciences Assistant Professor Heather Bean is launching a clinical study to learn if breath samples can lead to earlier diagnoses of lung infections in people with cystic fibrosis. She and graduate student Trenton Davis will be collecting 288 breath samples from five hospitals across the country. Photo by Samantha Lloyd/ASU VisLab

But there’s a conundrum

In children with cystic fibrosis (CF), the bacterial infections caused by pseudomonas aeruginosa are often not detected by using traditional tests. Left untreated, these infections flourish in a child’s lungs and can cause serious damage.

Heather Bean, Associate faculty at the Arizona State University Biodesign Center for Immunotherapy, Vaccines and Virotherapy and assistant professor with School of Life Sciences, is working to solve this problem. She and a group of collaborators have launched a new clinical study, with the hope of finding these infections sooner by using breath samples instead of invasive testing.

“Damage to their lungs is what kills most people with cystic fibrosis these days. It used to be that they died from malnutrition, but there have been some really good advancements in treatment,” said Bean, “People with this disease start getting lung infections in infancy and every time they get another lung infection, it’s causing damage. They’re treated with antibiotics as soon as the infections are detected but eventually, these therapies end up failing.”

The Cystic Fibrosis Foundation is providing three years of funding and the National Institutes of Health is providing an additional year of funding for Bean’s lab to start a clinical study that will determine whether pseudomonas aeruginosa infections can be detected from breath samples.

Diagnosing lung infections early

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disorder that is diagnosed through newborn screening. It’s characterized by thickened mucous secretions that are particularly damaging to the lungs, which can become clogged.

Clogged lungs are a great place for bacteria to multiply, making people much more susceptible to lung infections. Symptoms typically include frequent chest infections and difficulty breathing. Pseudomonas is the top threat to people with this disease because it’s aggressive and develops antibiotic resistance.

People with CF typically live into their mid-late 30s, and through research, life spans continue to improve. Early diagnostics help patients live longer, but the infections in children under 8 years old are typically diagnosed through throat cultures. Young children cannot reliably cough up enough mucus for a culture, like adults can.

“The problem is that little kids don’t have robust immune systems yet, so they might be infected but they aren’t showing symptoms,” Bean said. “They don’t necessarily have a fever, they don’t necessarily have increased cough, they aren’t necessarily losing weight, all these signs and symptoms that clinicians look for in adults who have CF.”

Thus, in order to reliably detect infections, young patients often have to have their lungs flushed and scraped, an incredibly invasive procedure.

What if, instead, all they had to do was breathe?

That is the solution Bean is striving for.

Finding answers in breath

During her postdoctorate research at Dartmouth College, Bean searched for chemicals produced by pseudomonas that could be used to identify it. She found that the infections did, in fact, produce unique chemicals that distinguish them from other bacterial infections.

First, she identified this in cultures and in mouse samples. Then, she was able to identify these chemicals in fluid samples taken from human lungs.

Now, she finally has funding to look for those same identifying chemicals in breath samples. She and her longest-tenured graduated student, Trenton Davis, will be collecting breath samples from 288 patients, ages 3 and older, from five different hospitals throughout the country. Then, they can determine whether the same chemicals that make pseudomonas identifiable in cultures are present in a patient’s breath.

Acute vs. chronic infections

In addition to their research on pseudomonas infections, Davis has been working with the lab’s current bacterial samples to detect differences between early (acute) and chronic infections.

“Typically, if we can catch the bacterium when it is colonized early in the patient, that leads to better outcomes. You have more options for antibiotics you can use,” Davis said. “If the patient has had that bacterium in their lungs for a while, that’s when you start seeing antibiotic resistance and that really cuts back on the choices of therapy you have.”

In another study, Davis found that while the same chemical signatures are present in both early and chronic infections, he found that the abundance of certain chemicals is different.

Searching for diagnostic solutions

Bean and her lab hope that, combined, this research will lead to faster and more accurate diagnoses of lung infections in cystic fibrosis patients. This would improve the quality of life and increase life span for patients with this disease.

Ultimately, Bean said it is the people she works with that makes her research so rewarding.

“These patients have seen the benefits of research during their lifetimes. They get new medicines that help them live longer,” Bean said. “They are so enthusiastic about participating in research studies and they’ll tell you it is the best part of their quarterly doctor’s visits. It’s been a real joy to directly interact with people who my work will benefit.”

The clinical study will be enrolling patients at five participating hospitals through 2021. If you are a patient at one of these facilities and would like to participate, ask your physician for details.

Written by: Melinda Weaver