Qiang “Shawn” Chenis an ASU Biodesign Institute researcher and School of Life School Sciences professor, Center for Infectious Diseases and Vaccinology.

Image Credit :Beth.Herlin – Wikimedia – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:ZIKA.png

Source Story: January 29, 2016

Qiang “Shawn” Chen

The World Health Organization warned Thursday (1/28/2016) that the Zika virus is “spreading explosively” in the Americas, and countries and health organizations are on full alert with emergency meetings taking place to prepare to halt the spread of the Zika virus.

WHO officials estimate that 1 million people are already infected in South America, and 4 million to 5 million more could be infected in 2016, as temperatures warm in the Northern Hemisphere.

About 51 people in the U.S. are currently infected, a result of recent travel to South America.

Of grave concern is the dramatic rise in Brazil of the number of cases of babies born with small heads, a rare condition called microcephaly. Though experts say it’s too early to prove that Zika has caused the condition, countries like El Salvador have gone to extreme measures — advising women not to get pregnant until 2018.

ASU experts are quickly mobilizing their efforts to understand the growing pandemic.

ASU Biodesign Institute researcher and School of Life Sciences professor Qiang “Shawn” Chen is a viral expert working on plant-based therapeutics and vaccines against West Nile virus, which comes from the same family of viruses as Zika. It’s the same approach Charlie Arntzen pioneered and used when he played a key role in developing ZMapp, the experimental treatment used during last year’s Ebola outbreak.

But for Chen, his motivation and efforts to innovate are also deeply personal — he watched his own father succumb to Japanese encephalitis virus, another notorious member of the flavivirus family.

Q: How did the Zika virus become such an emerging threat?

A: The Zika virus is transmitted to people through the bite of an infected mosquito from the Aedes genus, mainly Aedes aegypti in tropical regions. This is the same mosquito that transmits dengue, yellow fever, and as we saw last year, a virus called chikungunya. According to WHO data, the Zika virus disease outbreaks were first reported in the Pacific in 2007 and 2013 (on the islands of Yap and French Polynesia, respectively), and in 2015 in Brazil, Colombia and in Cape Verde in Africa. In addition, more than 14 countries in the Americas have reported sporadic Zika virus infections indicating rapid geographic expansion of Zika virus.

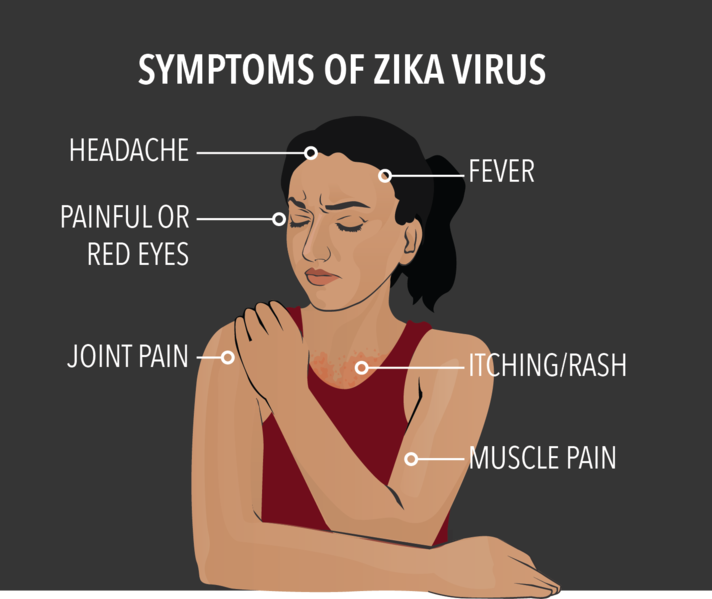

Q: What are the symptoms of a Zika infection, and how is it diagnosed?

A: Zika virus disease is usually relatively mild and requires no specific treatment. People infected with it typically develop a mild fever and have symptoms like a mild flu. Though you should always consult your doctor if you are concerned, in general people sick with Zika virus should get plenty of rest, drink enough fluids, and treat pain and fever with common medicines.

Zika virus is diagnosed through a test called PCR (polymerase chain reaction) and isolation of the virus from blood samples. But diagnosis by a blood test can be difficult as the virus can cross-react with other flaviviruses such as dengue, West Nile and yellow fever.

Q: How can we treat Zika?

A: Unfortunately, there is currently no vaccine or treatment available, which is why WHO and others have become increasingly alarmed, and are rightfully treating this as an emergency response and top emerging threat.

Q: How can women who are pregnant, or want to get pregnant, protect their fetuses?

A: While the infection is mild for adults, we know from past experience with West Nile and yellow fever that Zika can also attack the central nervous system. This has been linked to the spike in cases of the small-headed babies, which rightfully so has expectant mothers across the Americas very worried. But we still don’t know if Zika is the cause of microencephaly — it’s too early to tell.

Q: What is the anticipated threat to the Americas, and when do we expect to see Zika spread to the U.S.?

A: Since we already have a population of mosquitos that are able to transmit the virus and lots of movement between the U.S. and our infected neighboring countries, it’s very likely we will see limited Zika cases in the United States. Past experience with outbreaks of dengue and chikungunya, two viruses carried by the same mosquito, suggest that large-scale outbreaks of Zika in the U.S. may be unlikely. That’s because the U.S. has seen only sporadic spread of dengue and chikungunya, while they have spread widely in nearby countries. The main reason is that the mosquitoes that spread the virus are primarily found only in Southern states, and the U.S. does a much better job of protecting people from mosquitoes than other countries. However, this is a rapidly changing situation and the U.S. agencies will remain vigilant for any sustained transmission.

The best prevention is to reduce the number of mosquitos, and so we may see mass efforts of spraying of insecticides to lessen the threat. People can do everyday practical things like use insect repellent, wear long-sleeved clothes and empty any containers around their house that could hold water.

But we don’t know how this will play out yet — again, it’s too early. Because the symptoms are mild, it may become more widespread than West Nile or last year’s Ebola epidemic. And keep in mind, the virus could quickly mutate, and its health effects may vary from person to person.

Top photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture via Wikimedia Commons.

– See more at: https://biodesign.asu.edu/news/asus-dr-qiang-chen-what-expect-latest-global-health-concern#sthash.nGV9VxqK.dpuf